Some movies unite and arouse enthusiasm in both the most hardened critics and the general public. Movies that are remembered for many years to come, and that leave their mark on the viewer. Today, we’re going to talk about one such film. One that continues to receive praise decades after its release: Cinema Paradiso.

Giuseppe Tornatore directed this film that, in 1988, once again demonstrated that Italian cinema is still alive and capable of shining, even at the Oscars. Countless awards guaranteed its success, including the Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, the Golden Globe, four BAFTAs, and the Grand Jury Prize at Cannes.

Recently, Cinema Paradiso has returned to theaters, giving us an injection of hope in complex times. The movie itself evokes feelings of nostalgia. However, added to this is the recent loss of the incomparable Italian composer, Ennio Morricone, who wrote the film’s unforgettable soundtrack. In this article, we’ll take a look at some of the highlights of this ode to cinema and discover why, so many years later, it continues to unite the public.

A movie that talks about the movies

Art has always lent itself to reflection. For example, certain works end up deepening our thoughts about the work itself. In literature, this is known as metafiction or meta literature. In other words, a literary work or part of it that raises questions about its own nature, the act of creating the work, or its form.

This is something that we can also apply to cinema. After all, it’s a form of art and, consequently, reflections about its nature can be raised from the medium itself. There are various terms to refer to this type of cinematographic metafiction. The most popular are meta cinema or metafilm.

We’re talking about cinema that speaks or reflects on cinema itself in a general or a more particular way, attending to a specific question. Along these lines, are feature films such as 8½ (Fellini, 1963), Singing in the Rain (Donen and Kelly, 1952), Ed Wood (Burton, 1994), and even Pain and Glory (Almodóvar, 2019).

Cinema Paradiso is a clear example of meta cinema, since cinema is omnipresent throughout the film and, in fact, appears in various forms. In fact, cinema becomes the common thread, the nexus of all the plots, and one of the fundamental pillars of the life of its protagonist, Totò.

The story

Since his childhood, the protagonist has been fascinated by cinema. He’s also curious about the work of Alfredo, the projectionist of his town. With the passage of time, cinema acquires even greater relevance in Totò’s life. Indeed, as an adult, it becomes his profession, the center of his life.

Cinema Paradiso takes us back to those years when cinema was a real event. To the years when censorship was dedicated to cutting kisses or violent scenes. In addition, it takes us through all the different stages of its transition until finally, in the 80s, movie theaters had to be closed. Since then, new forms of consumption have been closing more and more cinemas over time. Furthermore, these new technologies have also been modifying certain professions, such as that of the projectionist.

In this way, the movie is a reflection on cinema itself, on those who make its projection in theaters possible, and those who enjoy it. Cinema Paradiso reflects on what cinema evokes, its evolution, and its magic over time.

Cinema Paradiso: A sentimental ode to cinema

As a viewer, you’ll find yourself watching a movie that reviews the history of the movies. Not only because of its constant references to Charlie Chaplin, films like Gone with the Wind, or even Italian cinema but also because of the roles of the movie theaters themselves.

For instance, you see how, in the summertime, they moved to open spaces. You witness the problems derived from projecting in two different sessions and two different places, and even the risk that the rolls of film caught fire if they weren’t careful.

Cinema Paradiso is a tribute to the public, to that first audience who couldn’t believe what they were witnessing. Cinema was their only form of entertainment. The movie theater was even the place where many experienced the awakening of their sexuality. You see both laughter and tears from the audience. You see the small booth where an illiterate projectionist sits who knows more about cinema than anyone else in his city.

Structure

The movie is structured in a poetic way, with exceptional staging and a soundtrack that, as we said earlier, is immortal. Ennio Morricone was a composer who gave us incomparable emotions. In fact, he was one of the many professionals who made sense of the complex world of cinema.

Cinema Paradiso highlights the last link in this entire human chain: the projectionists who made enjoyment possible in theaters and who’d previously sat through countless uncensored films in order to later show a censored version to the general public.

Although we didn’t live through that splendid era of cinema, Cinema Paradiso evokes its atmosphere perfectly and brings us closer to those first viewings. To an era when the Internet didn’t even exist and in which even television was a utopia.

It’s all accompanied by a background story, an extremely human tale. Nothing really exceptional happens in the movie, but the realism and detail with which Tornatore draws his characters and the performances of his actors make them beings with whom you soon start to empathize.

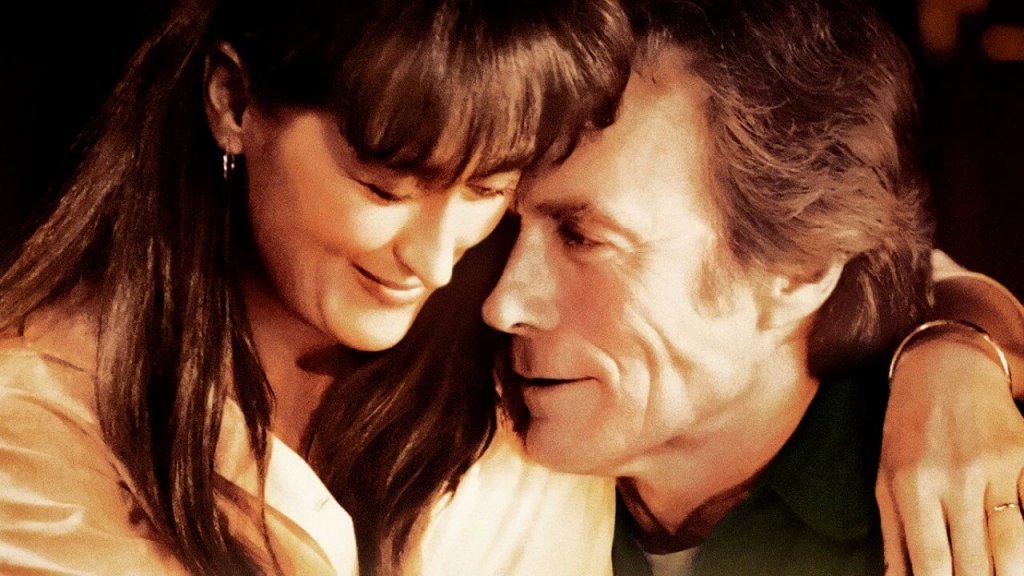

The relationship between Alfredo and Totò is the other great common thread. Their love of cinema unites them both and reaches its greatest expression through the most tragic moment of the film: Alfredo’s blindness. Naturally, there could be nothing worse for a projectionist and movie lover than losing their sight. This is why Totò becomes his replacement and, at the same time, Alfredo’s eyes.

From laughter to tears

Therefore, from laughter, the movie leads you to tears, to the emotion of cinema in its purest form as it invites you to accompany Totò throughout his life. You become a part of his close relationship with Alfredo, his first love, and his departure to the city. His return to his origins represents a contrast for Totò, a return to past emotions and nostalgia. In fact, it’s that nostalgic trip that makes Cinema Paradiso such a special film.

Movies invite you to dream and Tornatore invites you to enter this extremely special kind of dream that’s Cinema Paradiso.

In short, it’s a story where nothing particularly exceptional happens, but it has an extremely high sentimental component. It’s an ode, a love letter to cinema, and to all the professionals who continue to make it possible. It’s a standing ovation for the public and their reflections. Now, like Totò, 30 years after it was made, you’re able to enjoy this film again.

“Whatever you end up doing, love it.”

-Cinema Paradiso-

The post Cinema Paradiso: The Magic of The Movies appeared first on Exploring your mind.

Comments